‘A rotten foundation’: Design report unpacks historic, existing inequalities in nation’s highway system

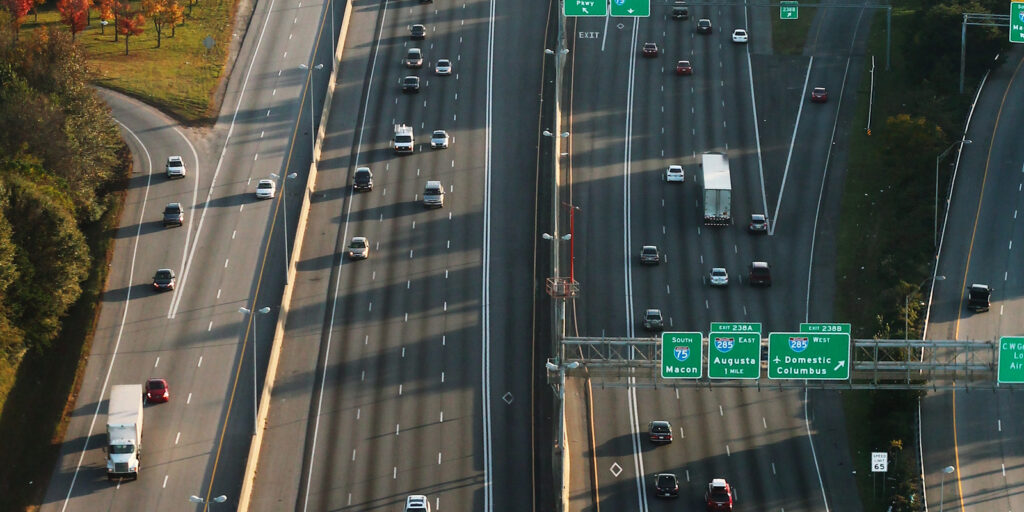

When it comes to weighing the benefits of a new highway or road against its cost, federal transportation administrators attempt to quantify the value of time. The potential time and monetary savings of those barreling down an existing or proposed thoroughfare often justifies the expenditure of taxpayer dollars—if millions of people can shave off a minute of their daily work commute, that’s millions of dollars saved.

Meanwhile, the transportation time and quality of life of those living in the neighborhoods that stand to be disrupted or destroyed by the roadway isn’t worth as much—if anything, based on federal cost-benefit guidance known as ‘value of time.’

“You can draw a direct line of measuring and assessing the ‘value of time’ to the 1960s,” said Steven Davis, assistant vice president of transportation strategy for Smart Growth America and co-author of the nonprofit’s recent report, “Divided by Design.”

Stemming from the evaluation system that was used when engineers bulldozed entire Black neighborhoods to build the nation’s Interstate Highway System, the ‘value of time’ criteria used to evaluate whether a modern roadway should be constructed or expanded “focuses primarily on work trips” while ignoring “other trips impacted”—like grocery runs or visits to the doctor made by local residents, he said. The economics of it are “fuzzy,” and time is scaled to income. “Wealthier commuters—who are more likely to be white in metro areas—saving their time is worth more in a dollar sense than lower income people.”

As a result, even when modern transportation officials seek to make equitable decisions, they’re working in a system that has “a rotten foundation. … Their intent really doesn’t matter. The system is broken.”

In substance, Smart Growth America’s “Divided by Design” report briefly examines the history of America’s highway system, then draws a line connecting modern transportation planning norms to practices used in the past, which were outright prejudicial, Davis said. It concludes with concrete policy suggestions that are mostly focused at the state and federal level. Local governments don’t often have a lot of sway, even if it stands to dramatically impact their constituents.

“What we’re hoping in this report, especially for local leaders to take, is to have the curtain lifted on how some of these projects are done in their communities,” Davis said. “It sometimes really doesn’t matter what the local community thinks, or what local leaders think.”

While repairing the damage done in the past by reconnecting communities, state departments of transportation should measure access to everyday needs and quantify the negative impacts of transportation investments, the report says. At the federal level, administrators need to clarify when high speed vehicle travel is appropriate and when it’s not—and prioritize the safety of everyone over the convenience of a few. Agencies also need to begin considering land use and transportation together, rather than separately.

Overhauling the ‘value of time’ assessment is a particularly important change noted by Davis. Technology enables planners to understand how long it takes local residents to drive to the store or access public transportation. There’s no reason to continue prioritizing commuter traffic at the expense of neighborhoods, housing and local businesses, which can’t just uproot and move elsewhere.

“A lot of it is inertia. The status quo is a powerful thing,” Davis said. “This is enormous machinery that operates to do these things—thousands and thousands of traffic engineers who have all been educated” in the same status quo-rooted way.

In this, Congress has an opportunity to make a substantial impact for good, he continued. However, because transportation is a perpetual and long-term need and lawmakers serve short terms, there isn’t a lot of incentive to change how things are done. Rather, short-term measures like the ongoing Reconnecting Communities and Neighborhoods Grant Program, are introduced.

“We will not repair the damage with a billion dollars,” Davis said, noting the Reconnecting Communities and Neighborhoods initiative is a good thing and “will do wonderful things in a few places.”

Meanwhile, annual investments continue into programs that maintain existing roadways that separate communities, and build new ones, clearing homes and businesses in the process.

“There’s a failure of imagination to imagine a world without a thing we’ve had forever,” Davis said, highlighting the negligible impact on traffic of a proposed highway in Atlanta that was never built. “We would be just fine. It would be a little disruptive to go from having it to not having it overnight, perhaps. We would also be fine.”